On the Thing Itself A Kula Manifesto

“We are always assailing ourselves for being the most materialistic culture on earth. But like almost everything else we say about ourselves, it is a half-truth. In this country, founded on an idea, I think “we” have mixed feelings about our things- though we may buy them compulsively; something in us hates them too. That’s the nasty secret behind the shoddiness of so much that we buy. We hate it. We want it to break and get dirty and wear out. We want to throw it away. And then, alas, we want to buy some more. We are like the uneasy smokers these days who, I notice, often throw their cigarettes to the ground after a few puffs. It is the lighting up that gives the pleasure. I sometimes wish we were more materialistic, not less. As it is, we like to buy more than we like to have. We take a nihilistic pleasure in obsolescence. Our country really needs to love the physical, tangible world more than it does, to care more about what it creates, buys, places on the earth.

People interviewed on television after a natural tragedy ravages their world- flood or fire or landslide- say, “It’s only things, and things can be replaced. Thank God everyone is safe.” And you admire them for this, as they expect you to, and their response is indeed right and good. But sometimes hearing these ritualistic lines, I get an unworthy, even coldhearted feeling. I want the things to be mourned. Many things, after all, survive us, and some deserve to, in part because they contain us.

Some other societies are perhaps a bit clearer on this idea. In the western Pacific, for instance, there is the concept of the Kula, which refers to the way in which objects accumulate value entirely on the basis of who has owned them. The objects themselves tend to be collections of shells that have little or no intrinsic worth, until they are passed from tribal leader to tribal leader, when they take on the luster of provenance. Any serious thinker in the West wanting to give things their due has to feel the chill gaze of Karl Marx, reminding us that capitalism has robbed things of their soul forever. But some anthropologists lately have begun to take a fresh, curious, and one may say humane attitude toward things, and toward consumption. In his wonderfully titled anthology The Social Life of Things, Arjun Appadurai advances the idea that it makes sense to think of things as having ”biographies”, passing through various identities, so that they indeed take on a life of their own. An object’s “exchange value” (the Marxist term) may thus over time be supplemented if not replaced by other meanings. “The commodity phase of the life history of an object does not exhaust its biography” he writes. This is not to say that most objects live outside of the economy altogether: Pricelessness is a luxury few objects can afford,” Appadurai observes. I suppose that small category would include a piece of the true cross or a teddy bear so battered by use that it’s market would consist of a single child. But many objects, perhaps all objects, whatever their price tag, occupy a larger economy of feeling and significance.”

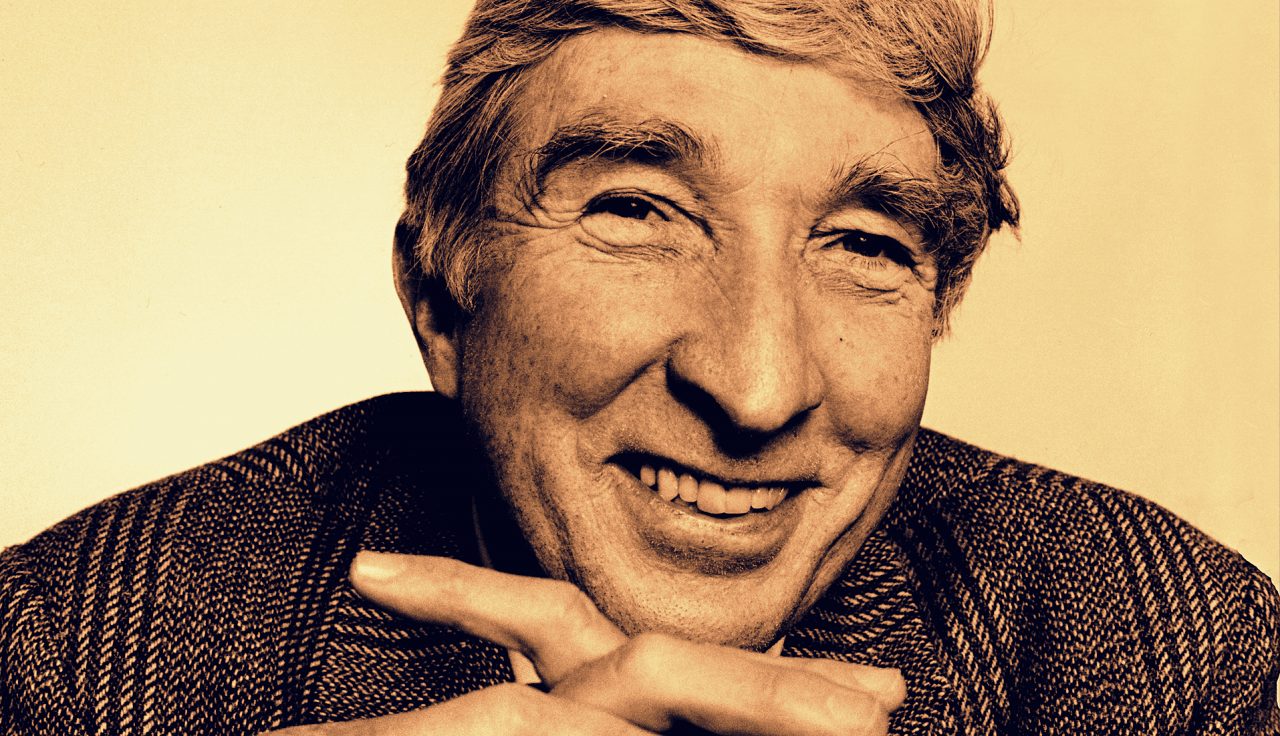

-THE THING ITSELF, On The Search For Authenticity By Richard Todd